Have you ever heard the saying, “Everything happens at the margin?” If you haven’t, you need more economist friends (joking!… kind of). If you have, you likely know they were talking about marginal analysis.

In economics, decision-making often revolves around evaluating the incremental changes that result from small adjustments in production, consumption, or investment. This process, known as marginal analysis, is essential for optimizing resources and maximizing benefits. Marginal analysis helps businesses, consumers, and policymakers make informed decisions by analyzing the effects of small changes on costs, benefits, and output.

In this post, we’ll explore the key concepts within marginal analysis, including marginal cost, marginal benefit, marginal revenue, marginal product, marginal rate of substitution, diminishing marginal returns, and marginal utility.

What is Marginal Analysis?

Marginal analysis is the examination of the additional or incremental changes in a given situation. These changes are usually associated with costs, benefits, utility, revenue, and other broader economic themes. The goal of marginal analysis is to find the optimal point – again, usually related to cost, production, etc. – so that businesses can make more informed decisions.

There are a few concepts that are key to marginal analysis. I keep them fairly high level below, but also include a link to more detailed posts if you would like to go deeper on any topic.

Marginal Cost (MC)

Marginal cost refers to the additional cost incurred by producing one more unit of a good or service. It’s an essential concept for businesses trying to determine the most cost-effective level of production.

The formula for marginal cost is:

Where:

- Change in Total Cost is the difference in cost after producing additional goods or services.

- Change in Quantity is the increase in the number of units produced.

In business, companies should aim to produce goods where marginal cost equals marginal revenue (more on that later), as this leads to profit maximization. If marginal cost exceeds marginal revenue, it may be time to reduce production.

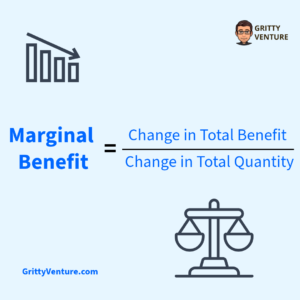

Marginal Benefit (MB)

Marginal Benefit is the additional satisfaction or value that a consumer receives from consuming one more unit of a good or service. For consumers, marginal benefit is used to determine whether it’s worth spending money on additional units of a good. The law of diminishing marginal utility states that as more units are consumed, the marginal benefit tends to decrease.

In a rational decision-making process, consumers will continue to consume until the marginal benefit of the last unit equals the price they pay for it.

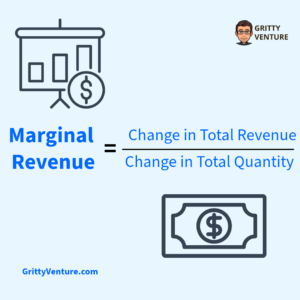

Marginal Revenue (MR)

Marginal revenue is the additional revenue generated from selling one more unit of a good or service. It is a crucial concept for businesses to determine the optimal quantity of goods to sell. In perfectly competitive markets, marginal revenue equals the price of the good, as the firm cannot influence the price. In monopolistic or oligopolistic markets, however, marginal revenue tends to be lower than the price of the good because the firm must lower the price to sell more units.

The formula for marginal revenue is:

Where:

- Change in Total Revenue is the difference in overall revenue received after selling an additional unit of a good or service.

- Change in Total Quantity is the increase in the number of goods or services sold.

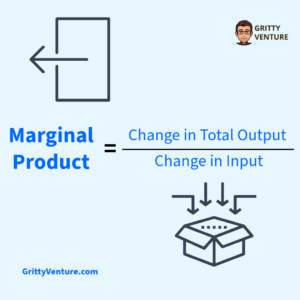

Marginal Product (MP)

Marginal product is the additional output produced when one more unit of a specific input (such as labor or capital) is added while keeping other inputs constant. This concept is essential for businesses to determine the optimal level of input. If marginal product is high, businesses may want to hire more workers or invest in more equipment to increase production. If marginal product starts to decrease, it might be a sign that additional inputs are becoming less efficient.

For example, in a factory setting, if adding a fifth worker increases output by 20 units, but adding a sixth worker only increases output by 10 units, the marginal product of the sixth worker is lower than that of the fifth.

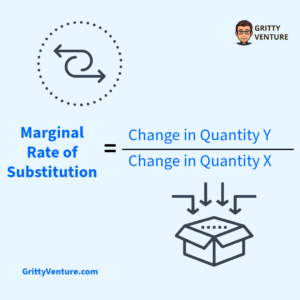

Marginal Rate of Substitution (MRS)

The marginal rate of substitution refers to the rate at which a consumer is willing to give up one good or service in exchange for another while maintaining the same level of overall satisfaction. It represents the trade-off between two goods that a consumer is willing to make. The concept is often used in the context of consumer theory and indifference curves, which show combinations of goods that provide the same level of utility to a consumer.

For instance, if a consumer is willing to give up 5 apples to gain one more banana while maintaining the same level of satisfaction, the marginal rate of substitution between apples and bananas is 5.

Diminishing Marginal Returns

The law of diminishing marginal returns states that as more units of a variable input (like labor or raw materials) are added to a fixed amount of other inputs (like machines or factory space), the additional output produced by each additional unit of input will eventually decrease. In other words, while adding more workers or resources initially increases output, at some point, each additional input will contribute less and less to total output.

This concept is crucial for businesses when deciding how much to expand production. Adding too many resources without increasing capital or infrastructure leads to inefficiencies, which can hurt profitability.

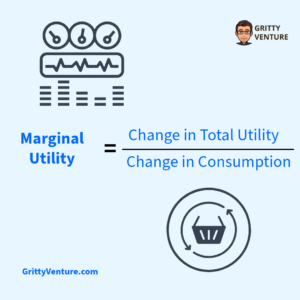

Marginal Utility (MU)

Marginal utility is the additional satisfaction or benefit a consumer receives from consuming one more unit of a good or service. According to the law of diminishing marginal utility, as more units of a good are consumed, the marginal utility decreases. This principle explains why consumers may not continue purchasing a product once the added satisfaction becomes less valuable than the price they are paying for it.

For example, after eating one slice of pizza, the satisfaction from consuming a second slice might be lower than the first. The marginal utility of the second slice is less than that of the first.

The Role of Marginal Analysis in Decision Making

Marginal analysis is a cornerstone of both individual and business decision-making. It helps individuals decide how much of a good to consume, businesses determine the optimal level of production, and policymakers set tax and subsidy rates to influence behavior. By comparing marginal costs and marginal benefits, businesses can make sure that their actions lead to maximum profit, while consumers can optimize their satisfaction with minimal expenditure.

In essence, marginal analysis is about making small, incremental adjustments to reach the most efficient and profitable outcomes. By applying these concepts, decision-makers can strike a balance between costs, benefits, and output, ensuring long-term success and growth.

Rules for Marginal Analysis: A Framework for Decision-Making

To effectively use marginal analysis, it’s helpful to follow these key rules:

Focus on the Margin

Always concentrate on the change resulting from one additional unit. Don’t get bogged down in total costs or benefits. Ask yourself: “What extra benefit will I get, and what extra cost will I incur, by doing one more?”

Compare Marginal Benefit to Marginal Cost

This is the heart of marginal analysis. Only make a change if the marginal benefit (MB) exceeds the marginal cost (MC).

Consider All Costs and Benefits

Be sure to include all relevant costs and benefits, both explicit (monetary) and implicit (non-monetary, like time or opportunity cost). Don’t overlook hidden costs or intangible benefits.

Ignore Sunk Costs

Sunk costs are costs that have already been incurred and cannot be recovered. They are irrelevant to marginal decision-making. Focus only on future costs and benefits. For example, if you’ve already paid for a non-refundable concert ticket, that cost is sunk. Your decision about whether to go to the concert should depend only on the marginal benefit of attending (enjoyment) and the marginal cost (travel time, etc.).

Recognize Diminishing Returns

Be aware of the law of diminishing marginal returns. As you consume or produce more of something, the marginal benefit will eventually decline. This means that even if MB > MC initially, it might not be true indefinitely.

Find the Optimal Point

The optimal point is where MB = MC. This is the point where you’ve maximized your net benefit (total benefit minus total cost). Any further increase will result in MB < MC, and any decrease will mean you’ve missed out on potential net benefits.

Be Aware of Your Assumptions

Marginal analysis often involves simplifying assumptions. Be aware of these assumptions and how they might affect your conclusions. For example, if you assume that prices will remain constant, but they actually change, your analysis might be inaccurate.

Use Marginal Analysis Iteratively

Marginal analysis is often an iterative process. You might need to adjust your decisions as you gather more information or as circumstances change.

Real-World Applications

Marginal analysis is used in a wide range of situations, including:

- Business Decisions: Should a company produce one more unit of a product? Should they hire an additional employee? At what point does increased production yield less profit per unit due to diminishing returns?

- Personal Choices: Should you study for one more hour? Should you eat one more slice of pizza? When does that extra hour of studying become less effective?

- Public Policy: Should the government invest in one more mile of highway? Should they provide one more year of education? Are the societal benefits of additional spending decreasing due to diminishing returns?

Examples

- Pizza: The first slice of pizza might be incredibly satisfying (high MB), but the fifth slice might not be as enjoyable (lower MB). If the cost of each slice is the same (constant MC), you’ll eventually reach a point where the MB of an additional slice is less than its MC. This illustrates diminishing returns.

- Studying: The first hour of studying might yield a big improvement in your understanding (high MB), but the fifth hour might not be as effective (lower MB). If the cost of your time is constant (constant MC), you’ll eventually reach a point where the MB of an additional hour of studying is less than its MC. Again, diminishing returns at play.

Limitations

While marginal analysis is a valuable tool, it’s important to remember that it’s based on estimations and assumptions. It can be difficult to accurately measure marginal costs and benefits in the real world. Additionally, marginal analysis doesn’t take into account factors like emotions, habits, or long-term consequences.

Bringing It Home

Understanding marginal cost, marginal benefit, marginal revenue, marginal product, marginal rate of substitution, diminishing marginal returns, and marginal utility is crucial for making rational decisions in economics. Whether you’re running a business, managing resources, or making personal consumption choices, marginal analysis helps you evaluate the trade-offs involved and find the best possible outcomes. Keep these concepts in mind, and you’ll be better equipped to navigate the world of economics and make more informed, strategic decisions.